Isaac or Ishmael? A Comparative Study of the Abrahamic Covenant in Islam and the Bible

1. Why Islamic Scholars Believe the Torah Was Altered Regarding Ishmael

The Qur’an accuses some Jewish scribes of altering scripture:

“Do you hope they will believe you, when some of them used to hear the words of God then distort them after they had understood them, knowingly?” (Qur’an 2:75)

“So woe to those who write the Book with their own hands and then say, ‘This is from God,’ to exchange it for a small price.” (Qur’an 2:79)

This doctrine of taḥrīf (distortion) is applied by Muslim exegetes to the Abrahamic covenant narratives. They argue that the Torah originally gave Ishmael covenantal prominence, but Jewish scribes altered the text to place Isaac in that role for political and ethnic reasons:

• Ethnic exclusivity: Restricting the covenant to Isaac made it Israel’s exclusive inheritance.

• Religious authority: Elevating Isaac justified Israel’s claim to be God’s sole chosen people.

• Arab-Israelite rivalry: Excluding Ishmael delegitimized the Ishmaelites (later Arabs) as covenantal heirs.

⸻

2. Islamic Reasons Supporting Ishmael’s Role

a. Qur’anic Testimony

• Universal covenant: Abraham was promised leadership for his descendants, but God limited it to the righteous, not by bloodline (Qur’an 2:124). Ishmael qualifies.

• The Sacrifice Narrative: Qur’an 37:101–112 implies the sacrificed son was Ishmael, since Isaac’s birth is mentioned after the sacrifice story.

• Kaaba (House of God) and prayer for Ishmael’s descendants: Abraham and Ishmael built the Kaaba and prayed for a messenger from their line (Qur’an 2:127–129) — fulfilled in Muhammad ﷺ.

• Praise for Ishmael: The Qur’an honors Ishmael as a prophet and covenant-keeper (Qur’an 19:54–55).

b. Historical logic

• Firstborn son: By ancient Near Eastern custom, Ishmael (the firstborn) should have been covenantal heir unless disqualified — but the Bible itself shows God blessing him greatly (Genesis 17:20).

• Circumcision: Ishmael was circumcised at the age of 13, on the same day as his father Abraham, and before Isaac was born (Genesis 17:23–25). This means that Ishmael entered the covenant earlier than Isaac. Therefore, the theological importance of Isaac’s circumcision is similar to that of the other members of Abraham’s household.

• Sacrificial test: Islam preserves Ishmael’s central role in the great test of faith, commemorated annually at Eid al-Adha. Judaism and Christianity, in contrast, have no liturgical commemoration of Isaac’s binding (Akedah), which Muslims see as a sign of textual alteration.

⸻

3. Biblical Reasons that Support the Islamic Assertion

Even within the Bible, there are tensions and clues that suggest Ishmael’s role was more significant than later scribes allowed:

1. Ishmael is blessed to become a “great nation”

• “As for Ishmael, I have heard you. I will surely bless him; I will make him fruitful and will greatly increase his numbers. He will be the father of twelve rulers, and I will make him into a great nation.” (Genesis 17:20)

This blessing closely parallels covenantal promises given to Isaac.

2. Circumcision before Isaac

• Genesis 17:23–25 explicitly records Ishmael’s circumcision as covenantal sign, before Isaac’s birth. This raises the question: why would the covenant sign be given to one excluded from it?

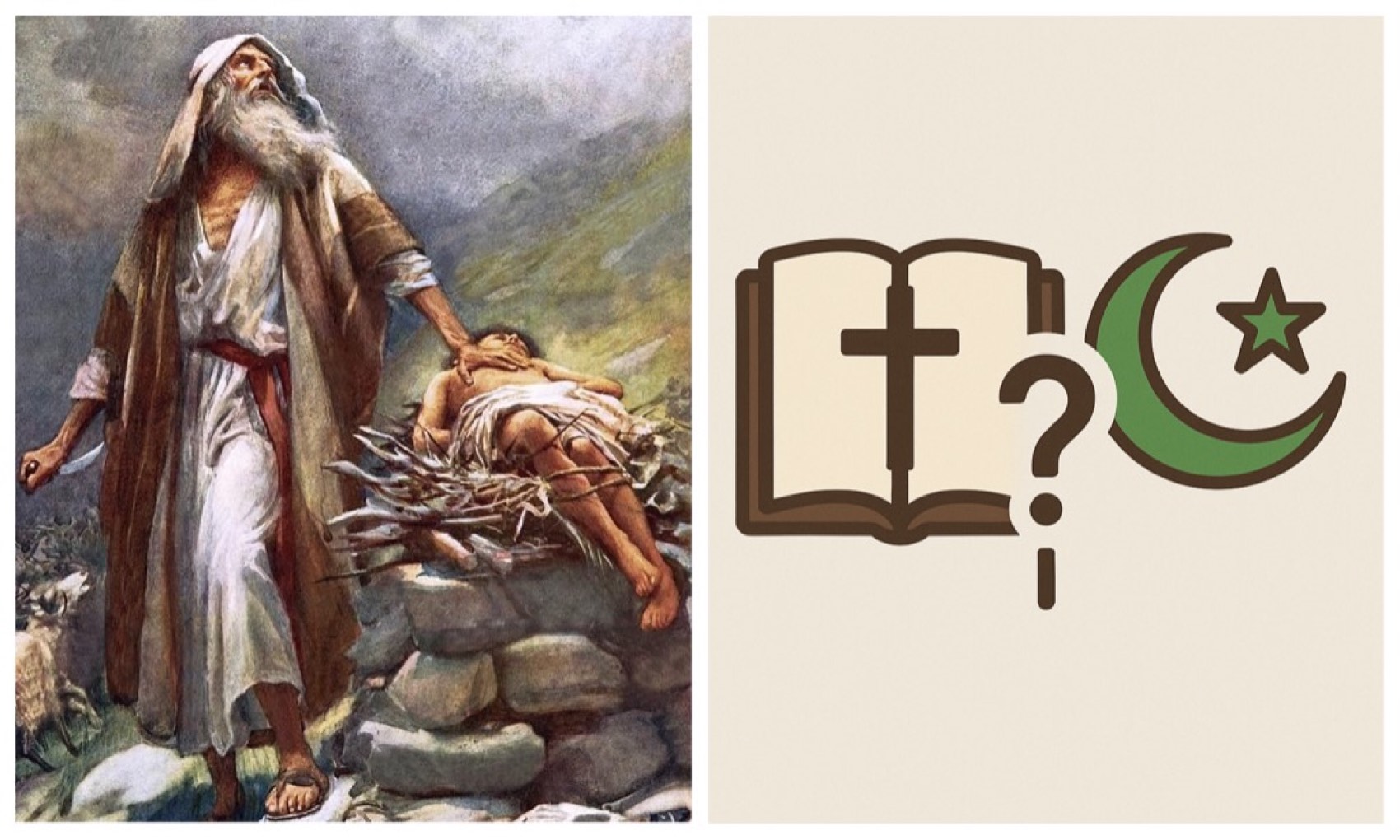

3. Ambiguity of the Sacrifice Story

• In Genesis 22:2, Isaac is named as the son to be sacrificed. But Muslim scholars argue this insertion is suspicious because:

• Earlier verses (Genesis 22:1) simply say “your son, your only son” — which could only have referred to Ishmael at the time, since Isaac wasn’t born until later.

• The phrase “your only son” makes no sense if Isaac is meant, because Ishmael was alive. Thus, the text seems edited.

4. No Jewish Festival for the Binding

• Despite its centrality, Judaism has no feast commemorating Isaac’s binding, whereas Islam preserves its memory through Eid al-Adha. This absence suggests the Isaac-centered version was secondary.

5. Arab traditions of Abraham and Ishmael

• Pre-Islamic Arabs preserved traditions of Abraham and Ishmael at the Kaaba (House of God) in Mecca. This continuity indicates Ishmael’s role was widely remembered outside of Jewish editing.

⸻

4. Ishmael as a Baby: A Biblical Contradiction

The book of Genesis presents Ishmael in a way that appears inconsistent with the chronological details of the narrative:

• Genesis 21:14–18: Abraham sends Hagar away with bread and water, placing the child on her shoulder as though he were an infant. Later, Hagar lays Ishmael under a bush, unable to watch him die of thirst, until an angel instructs her to “lift the boy up.”

• Genesis 21:20: The text continues, “And God was with the boy as he grew,” which further suggests an image of early childhood.

Yet, according to the timeline, Ishmael would have been around 16–17 years old at this point (Genesis 16:16; 21:5). The description of him as a helpless baby therefore introduces a contradiction within the Biblical account.

Importantly, this very portrayal aligns with the Islamic perspective: Ishmael was still an infant when Hagar left Abraham’s household and settled in the valley of Makkah, where God provided for them. Thus, the Biblical imagery of Ishmael as a young child, though inconsistent with its own chronology, indirectly supports the Islamic tradition that situates his expulsion in infancy.

Conclusion

The ambiguous wording of the sacrifice narrative—where the phrase “your son, your only son” could only have referred to Ishmael at that time—and the fact that Ishmael was circumcised alongside Abraham before Isaac’s birth, strongly indicate his covenantal significance. These elements suggest that Ishmael was indeed a rightful heir of the Abrahamic covenant, but the text was later shaped to elevate Isaac while diminishing Ishmael’s original role.

The contradictions within Genesis — portraying Ishmael as both a teenager by chronology and as a helpless baby by narrative — point to possible textual reshaping intended to diminish his stature in favor of Isaac. At the same time, this very imagery, whether intentional or not, indirectly supports the Islamic belief that Ishmael was in fact an infant when he left Abraham’s household with Hagar.

Islam affirms that Ishmael was never rejected. Instead, he was a prophet, covenant-bearer, and forefather of Muhammad ﷺ. Through him, the Abrahamic covenant found its universal fulfillment, not confined to one lineage but extending to all nations through Muhammad and the message of Islam.