”Who Wrote the Bible? Unraveling the Origins of the Sacred Text“

For more than two thousand years, the Bible has stood at the heart of Western civilization — shaping faith, philosophy, literature, and law. Yet despite its universal influence, a fundamental question persists: who actually wrote it?

“In Who Wrote the Bible?”, biblical scholar Richard Elliott Friedman traces this mystery through centuries of investigation, revealing that the Bible is not the work of a single hand but a tapestry woven from multiple voices across hundreds of years.

From Tradition to Investigation

For centuries, both Jewish and Christian tradition maintained that Moses wrote the first five books — Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy — collectively known as the Torah or Pentateuch. However, inconsistencies within the text—such as repeated stories, contradictory timelines, and the account of Moses’s own death—challenged that belief.

Scholars across time, from medieval rabbis like Ibn Ezra to Enlightenment philosophers like Spinoza, began to recognize that these books contained multiple distinct styles, vocabularies, and perspectives, suggesting multiple authors.

The Discovery of the Four Sources

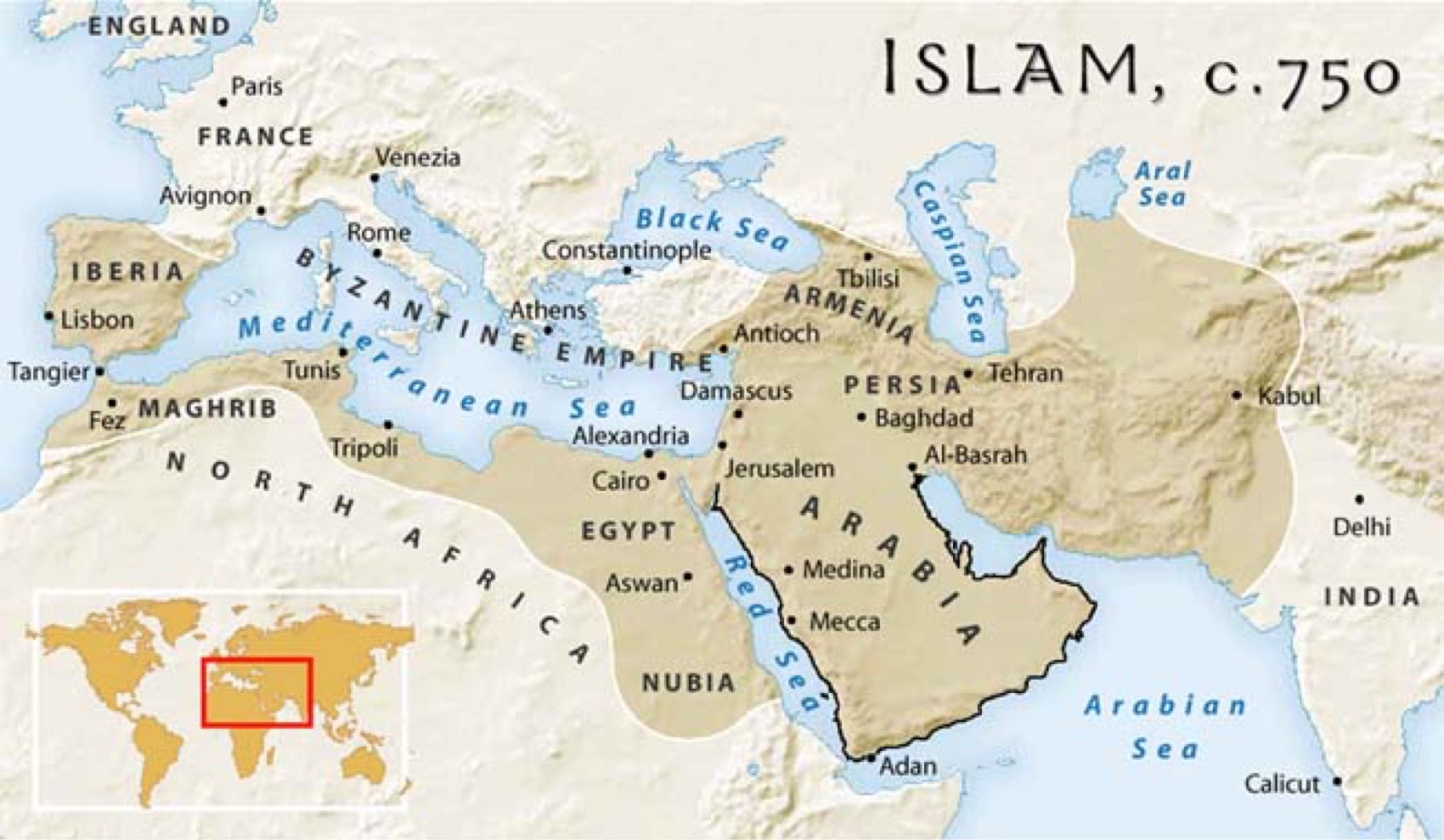

By the 19th century, biblical scholars identified four major literary sources behind the Torah, each representing a different time, community, and theological viewpoint. Friedman details how these sources were ultimately woven together by later editors into the unified narrative we now call the Bible.

1. J – The Yahwist (Earliest, c. 950 BCE)

Region: Southern Kingdom of Judah

Divine name used: Yahweh (Jehovah)

Tone: Earthy, vivid storytelling; emphasizes humanity and the closeness of God

Themes: God as directly involved in human affairs; focus on Judah’s royal line, especially David

Historical Context: Likely written during the early monarchy when Judah flourished under David and Solomon

2. E – The Elohist (c. 850 BCE)

Region: Northern Kingdom of Israel

Divine name used: Elohim (God)

Tone: More abstract, moralistic, and distant portrayal of God

Themes: Focuses on prophets, dreams, and moral testing (e.g., Abraham and Isaac); favors northern heroes like Joseph

Historical Context: Written in a time of tension between the northern and southern kingdoms, showing Israel’s distinct identity

3. D – The Deuteronomist (c. 622 BCE)

Region: Jerusalem, during the reign of King Josiah

Divine name used: Yahweh

Tone: Preaching, legalistic, reform-oriented

Themes: Centralization of worship in Jerusalem, covenant loyalty, divine justice

Historical Context: Likely written during Josiah’s religious reforms, when the “Book of the Law” was rediscovered in the Temple (2 Kings 22). This source forms nearly all of the book of Deuteronomy.

4. P – The Priestly Source (Latest, c. 550–400 BCE)

Region: During or after the Babylonian Exile

Divine name used: Elohim (early on), later Yahweh

Tone: Structured, ritualistic, concerned with laws, genealogies, and priestly duties

Themes: Emphasizes holiness, sacred order, ritual purity, and the authority of the priesthood

Historical Context: Composed when Israel’s identity was in crisis during exile; aimed to preserve religious traditions and priestly authority

Together, these four documents form the Documentary Hypothesis, which holds that the Pentateuch is a composite of these sources, edited into one continuous story by later redactors.

From Controversy to Acceptance

Initially, these discoveries were met with fierce opposition. Religious authorities denounced scholars who challenged Mosaic authorship — from Spinoza’s excommunication to John Colenso’s condemnation as “the wicked bishop.” But over time, evidence prevailed.

By the mid-20th century, even the Catholic Church, once cautious about historical criticism, encouraged scholarly study of the Bible’s human authors. Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu invited researchers to explore “the sources and the peculiar character of the sacred writers.”

The Earliest and the Latest Voices

According to Friedman’s synthesis:

The earliest biblical writings emerged around 950 BCE (J) in Judah, painting a vivid, personal vision of God’s relationship with humanity.

The latest writings (P) appeared nearly five centuries later (c. 500–400 BCE), after the Babylonian exile, systematizing worship and laws to preserve Israel’s faith and identity in a foreign land.

Thus, the Bible evolved over roughly half a millennium, reflecting a dialogue across generations — from storytellers and prophets to priests and reformers.

A Human and Divine Collaboration

Friedman concludes that understanding the Bible’s human authors does not undermine its sacredness — it deepens it. Knowing that the text was forged in the fires of history, politics, and faith allows modern readers to see it as a living conversation between humanity and God, across centuries of change.

Conclusion

“Richard Elliott Friedman’s Who Wrote the Bible?” transforms a mystery of faith into a story of human creativity and divine inspiration. The Bible emerges not as a monologue dictated from heaven, but as a chorus of voices — from the Yahwist poet of Judah to the priestly scribes of the Exile — each adding depth, struggle, and beauty to the world’s most influential book.