Khazar

The history of this Khazar conversion to Judaism is recorded in many Jewish, Christian and Arab sources. Koestler’s book includes the 10th century correspondence between Joseph the King, or Khagan, of Khazaria and Hasdai Ibn Shaprut of Cordova, a Jewish doctor and foreign minister to the court of Sultan Abdu al-Rahm, the Caliph of Spain.

The letters were first published by the Jews themselves in 1577. Koestler records how the rabbi, Judah Halevi, knew of the letters even in 1140. Koestler’s book relates the story of how, around 930 AD, Hasdai Ibn Shaprut became aware of a Jewish nation north of the Caucusus mountains through merchants from the region coming to Spain and decided to send letters back with them to the Kagan of Khazaria to find the truth of the matter.

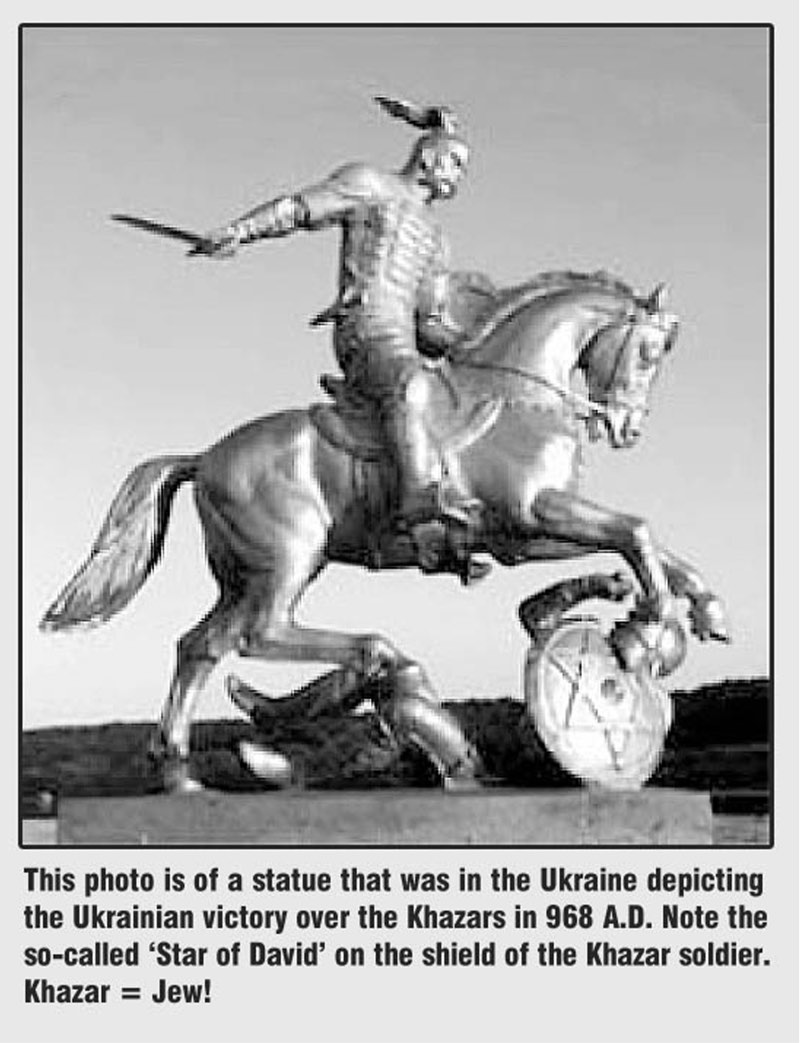

Shaprut thought that maybe they were some of the lost tribes of Israel that had gone into Assyrian captivity in 722 BC, and asked the Khagan if this was the case. Khagan Joseph responded that they were not the lost tribes of Israel but had descended through Khazar, son of Togarmah, son of Magog, son of Japheth. This meant that they had no Semitic bloodline at all for the Semites trace their genealogy through Shem the brother of Japheth.

Here is how Koestler relates the reply from King Joseph of Khazaria to Hasdai Ibn Shaprut: “Joseph then proceeds to provide a genealogy of his people. Though a fierce Jewish nationalist, proud of wielding the “scepter of Judah,” he cannot, and does not, claim for them Semitic descent; he traces their ancestry not to Shem, but to Noah’s third son, Japheth; or more precisely to Japheth’s grandson, Togarma, the ancestor of all Turkish tribes. “We have found in the family registers of our fathers,” Joseph asserts boldly, “that Togarma had ten sons, and the names of their offspring are as follows: Uigur, Dursu, Avars, Huns, Basilii, Tarniakh, Khazars, Zagora, Bulgars, Sabir. We are the sons of Khazar, the seventh...”

This is rather amazing, since Koestler points out that the majority of Jews in the world, the Ashkenazi, who compose about 90% of worldwide Jewry, owe their great population advantage over the Sephardic Jews due to this great influx of probably half a million Khazar Turks converting to Judaism. This has got to be one of the greatest ironies in history. For not only are the Ashkenazi the loudest voices screaming anti-Semitism, they are the one who initiated political Zionism to ‘return’ to the ‘promised land’—a land in which the majority of their forefathers never even had put one toe in!