Interpolation in the Torah from an Islamic viewpoint

Here is how the Jewish scribe manipulated Ishmael's story:

1. The age of Ishmael at the time of his departure from Abraham's house.

2. Abraham's son, who was offered as a sacrifice.

Some Islamic scholars suspect that the scribes tampered with the story of Hagar and Ishmael in the Torah. It is argued that Genesis 21, verses 9 to 10, may have been added later because Ishmael and Hagar had already left Abraham's house long before Isaac was born, with Ishmael being an infant according to Islamic tradition.

Similarly, some question whether Genesis 22, verse 2, could refer to Ishmael, since Isaac had never been Abraham's only son, whereas Ishmael had been for fourteen years before Isaac was born. How is this Islamic viewpoint presented?

The Islamic perspective on the stories of Hagar, Ishmael, and Isaac, as presented in the Torah, differs significantly from the Jewish and Christian narratives. These differences have led some Islamic scholars to question the authenticity of certain Biblical passages, suggesting possible later additions or alterations.

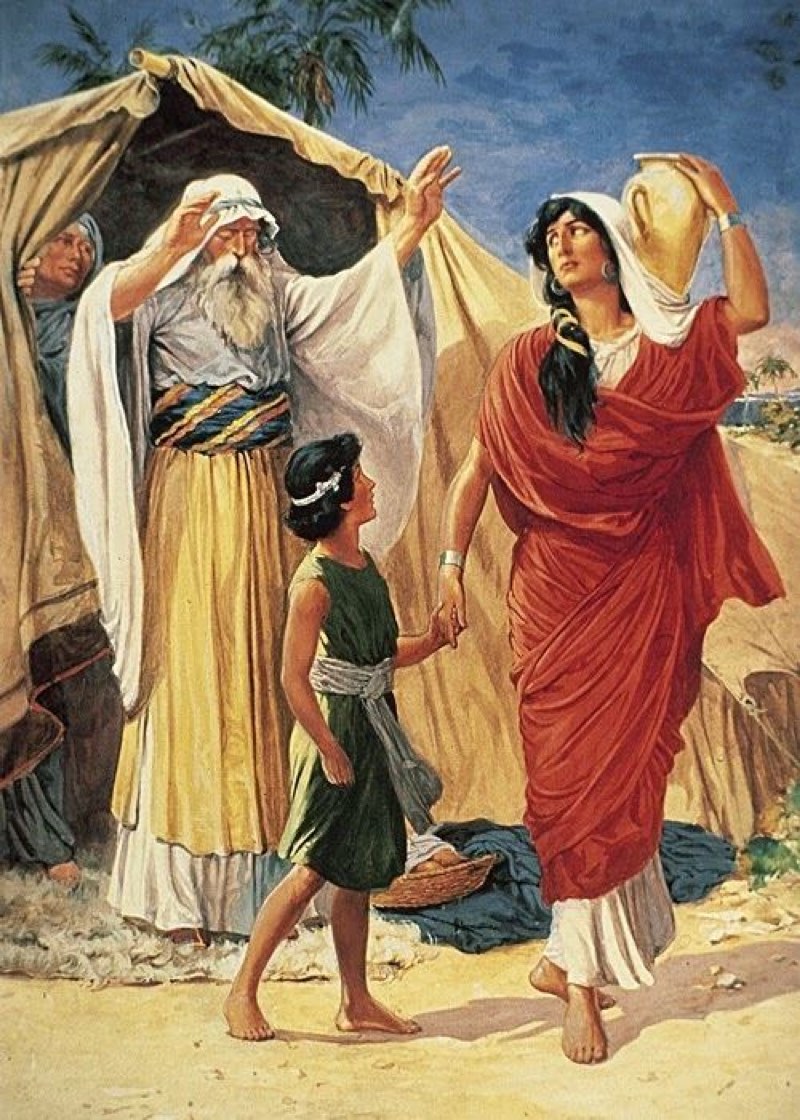

In the Islamic tradition, Hagar and Ishmael's story is seen through a different lens compared to the Biblical account. According to Islamic belief, Ishmael was an infant when he and his mother Hagar were left in the desert, which contrasts with the Biblical narrative where Ishmael is depicted as a young boy during this event.

Some Islamic scholars argue that certain verses in Genesis, such as Genesis 21:9-10, might have been added later, as they imply that Ishmael was older and capable of mocking Isaac, which would not align with the Islamic timeline where Ishmael had already left before Isaac's birth.

The question of who was the intended son of sacrifice is another point of divergence. In the Quran, it is generally believed that Ishmael was the son whom Abraham was commanded to sacrifice, whereas the Bible identifies Isaac as the intended sacrifice.

This discrepancy has led some Islamic scholars to suggest that Genesis 22, verse 2, which refers to Isaac as Abraham's "only son," might be inaccurate, as Ishmael was Abraham's firstborn and was his only son for fourteen years before Isaac's birth. The argument is that the description of Isaac as the "only son" could have been a later addition to emphasize Isaac's significance in the Jewish tradition.

Islamic narratives emphasize the significance of Ishmael and his descendants, linking them to the lineage of the Prophet Muhammad. The Islamic tradition holds that Abraham and Ishmael together built the Kaaba in Mecca, a central element in Islamic faith, which is not mentioned in the Bible. The Quran and Islamic teachings often highlight the spiritual and prophetic roles of both Ishmael and Isaac, but with a focus on Ishmael's role in the lineage leading to Islam.

Conclusion

The Islamic viewpoint on the story of Hagar and Ishmael in the Torah is characterized by skepticism towards the authenticity of certain verses. Islamic scholars argue that the timeline and events described in the Torah may have been altered, and that Ishmael may have been the son referred to in Genesis 22:2 instead of Isaac.